October 2025

Biodiversity

The fever tree’s golden secret

in BiodiversityShare:

The fever tree’s golden secret

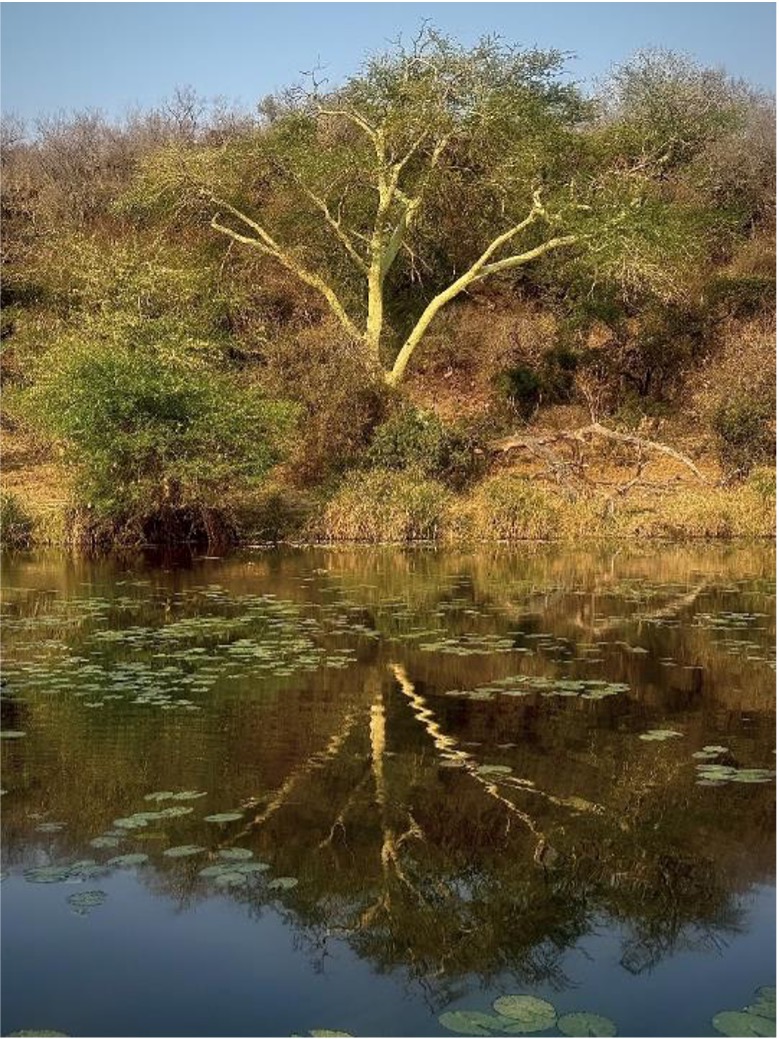

There’s a certain light that fills the bushveld when the morning mist lifts off the river, and the first sun rays touch the bark of a fever tree. It’s a pale gold, almost luminous — a kind of glow that makes these trees seem alive with their own quiet energy. Here along the N’wanetsi River, the fever trees (Vachellia xanthophloea) stand like guardians of the water, their reflections rippling in the slow current.

Most guests are struck by their colour first — that smooth, yellow-green bark so unlike anything else in the savanna. But the fever tree’s brilliance is not just skin deep. Its presence tells us a story about water, life, and ancient beliefs that have flowed through this land for generations.

The ecology of the fever tree:

Fever trees favour riverbanks and seasonal floodplains — places where the soil stays moist long after the rains have gone. Their roots stretch deep into the alluvial layers, drawing from the steady underground supply. These fertile, oxygen-rich soils nurture not just the trees themselves but a host of life around them: vervet monkeys leaping between branches, herons roosting in the canopy, and even hippos resting in their shade during the hottest hours. By binding the riverbanks, fever trees prevent erosion, holding the land together during the torrent of summer storms. In a sense, they are the park’s natural engineers — quiet custodians maintaining the delicate balance between land and water. And where fever trees grow, the ecosystem hums with vitality.

The spirit of the tree:

Among the local Tsonga and Shangaan people, the fever tree carries meaning that goes beyond ecology. Its yellow bark, when ground into a fine powder, is sometimes used in traditional rituals as a muthi — a good luck charm. Elders say that this golden powder can attract prosperity, protect travellers, and open the path for new beginnings. Hunters once rubbed a little on their foreheads before setting out, believing it would bring success and safety on the journey. But with all such beliefs, there’s respect. One doesn’t simply take from the fever tree. A small offering — a song, a whispered greeting, a sprinkle of river sand — is given before collecting its bark. The tree, they say, holds the spirit of the river itself, and taking from it without gratitude may anger the ancestors.

The fever tree and its misunderstood name:

Interestingly, the name “fever tree” came from early European settlers who noticed that malaria was common in areas where these trees grew. They thought the trees caused the fevers, not realizing that the real culprit was the mosquito that also favoured these swampy habitats. In truth, the fever tree was not the cause of sickness but a sign of life — a signal that water, and therefore mosquitoes, were nearby.

A golden thread:

Today, as I guide guests beneath their luminous canopies, I like to think of fever trees as bridges — between science and story, between ecology and belief. They remind us that the bush is not just a landscape of animals and plants, but a living tapestry woven with meaning. When the wind rustles through their leaves at dusk, and the light fades into that soft African gold, I sometimes catch the scent of dust and sap and river air — and I understand why our elders say the fever tree brings luck. Standing beneath one, it’s impossible not to feel blessed.

By Walter Mabilane

Field Guide